Biological Clocks in Mosquitoes

|

An important malaria vector species of primarily South

Asia, found between latitudes 10°N and 35°N. The type locality was

Ellichpur, Central Provinces, India. Its northern limits probably are

defined by the 10°C isotherm, as at that temperature development

effectively ceases and eggs will not survive exposure to lower

temperatures for more than two weeks (Lal, 1953; Stone et al.,

1959; Al-Tikitry, 1964). Daggy (1959) found that in the oases of Saudi

Arabia the adult females sheltered by day and fed only after sunset.

An important malaria vector species of primarily South

Asia, found between latitudes 10°N and 35°N. The type locality was

Ellichpur, Central Provinces, India. Its northern limits probably are

defined by the 10°C isotherm, as at that temperature development

effectively ceases and eggs will not survive exposure to lower

temperatures for more than two weeks (Lal, 1953; Stone et al.,

1959; Al-Tikitry, 1964). Daggy (1959) found that in the oases of Saudi

Arabia the adult females sheltered by day and fed only after sunset.

Experimental material

The adults were reared, under LD 12:12, from eggs obtained from the

Ross Institute of Tropical Medicine, where a colony originating from

near Delhi, India (28°39'N), had been maintained since 1950. The colony

was of the strain StSSDPI.

Experimental regimes

LD 8:16 to LD 4:20, nine females, studied from 3 days

post-emergence (18 October 1968). Recorded in LD 8:16 for days two to

five then light-on delayed 4h to give LD 4:20 until day eight.

LD 12:12 to LD 16:8, nine females, studied from 3 days

post-emergence (18 October 1968). Recorded in LD 12:12 for days two to

four then light-on advanced 4h to give LD 16:8 until day eight.

LD 20:4, nine females, studied from 5-6 days post-emergence (24

October 1968) and recorded for days three to six.

Results and discussion

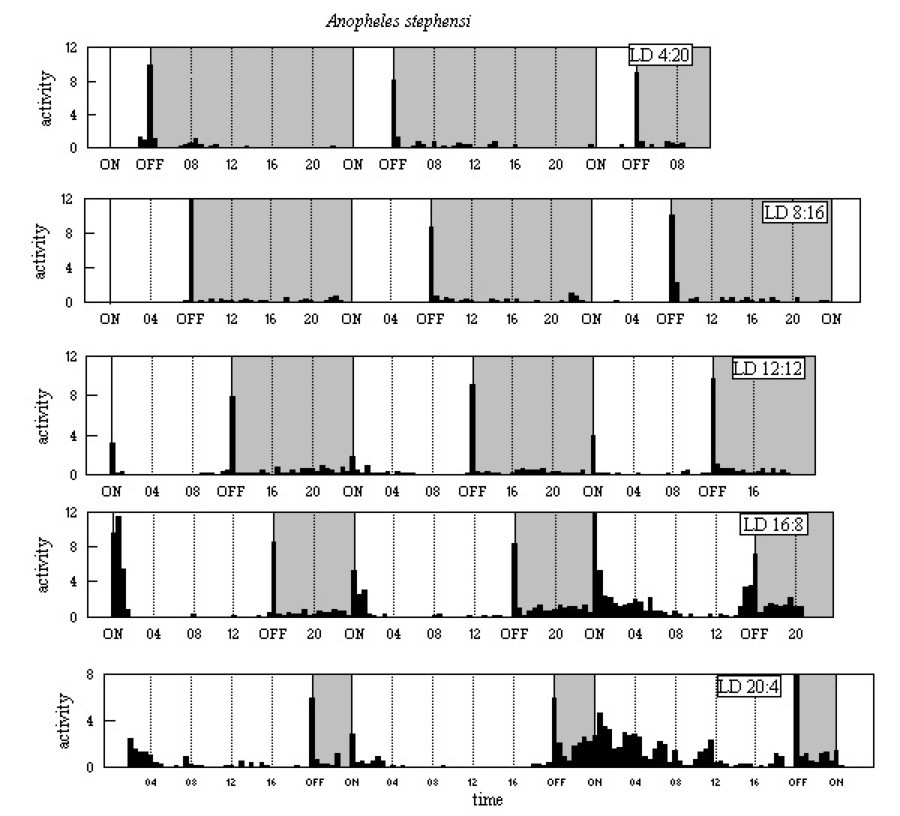

The activity patterns are shown in Figure A9 below. In all five LD

regimes there is a major E peak, with low level activity

through much of the dark period. M peaks are clear at light-on

in LD 12:12 and LD 16:8, and there is a response to light-on in LD

20:4. The continuation of activity after light-on in LD 20:4, specially

in the second 24h cycle, may suggest that M is more than just

a startle response to light-on.

Figure A9

From field studies in Punjab Province, Pakistan (approx. 32°N), Reisen

& Aslamkhan (1978) found that the peak of biting was markedly

crepuscular during periods of low ambient temperature (i.e. a peak at

1800-1900h in November to February) but this shifted with increasing

ambient temperatures, being around 2200-2300h in May to July.

Jones (1974) recorded An. stephensi flight activity in the laboratory. His results in LD 12:12 also showed the bimodal pattern, with a strong E and a lesser M, seen in Figure A9 and previously outlined by Taylor (1969a, b). He found additionally that, in DD following LD 12:12, there was a clear circadian rhythm, although only E persisted, with a circadian period t < 24h. Using LD 12:12 to 24h L to DD, the activity was reset by light-off and the new rhythm persisted.

More recently, Rowland (1989) has used the acoustic technique to examine several aspects of the An. stephensi flight activity. His work differed in using a regime with light of 40 lux and "dusk" simulated by a transition period dimming the light to 0 lux over a period of one hour. The transition from L to D was measured at an undefined mid-point, presumably 20 lux. Changes in the flight activity pattern associated with insemination, blood-feeding, oviposition and nocturnal light intensity (artificial moonlight) were detected by recording the patterns before and after mating, and throughout the gonotrophic cycle. Males and virgin females showed only E activity in LD 12:12. After insemination females exhibited an E peak followed by short bursts in the night (similar to those shown in Figure A9). After blood-feeding the females were inactive for two nights, but once gravid there was strong E activity and lesser activity later in the night. After oviposition the females resumed the post-mating pattern. The effect of simulated moonlight was an apparent movement of E and enhanced, prolonged N activity. Rowland also found a circadian rhythm in DD, with t @ 24h.

|

©1998, 2010 - Brian Taylor CBiol FSB FRES 11, Grazingfield, Wilford, Nottingham, NG11 7FN, U.K. Comments to dr.b.taylor@ntlworld.com |

href="\crhtml\ansteph.htm"