The History of the Parish Church

of St. Mary the Virgin, Nottingham

St. Mary's Nottingham, two Williams and a cross pomeé - continuation

Background

| Although the site was probably in Christian

use before the Norman invasion and equally probably the church was the

one listed in the Domesday Record, few firm records exist prior to the

description by Leland, who visited Nottingham in 1534. He wrote how St.

Mary's was - "excellente [new] and unyforme yn worke and so

manie faire wyndows yn itt yt no artificer can imagine to get more".

But, how new was it and who was responsible for the construction of such

a magnificent building?

Unfortunately there is a scarcity of early records, which can be

attributed to the loss of the Cartulary of the Cluniac Monastery of

Lenton. Lenton had been granted St. Mary's, together with the churches

of St. Peter and St. Nicholas in the new French Town, in 1103-8 by

William Peveril, with the consent of the Lord King, Henry I. The

copper engraving of St. Mary's by Wenceslaur Hollar (1607-77), based

on a drawing by Richard Hall, and first published by Dr. Robert

Thoroton in 1677 (Thoroton, 1677) is of great importance. This shows

how the subsequent restorations were essentially faithful to the

original; even the 19th Century work ascribed to Sir Giles Gilbert

Scott, later renowned for his over-restorations of many churches,

although the building work was actually overseen by Moffatt and the

style also followed that used by William Stretton, who did much

rebuilding in the early years of the century. |

|

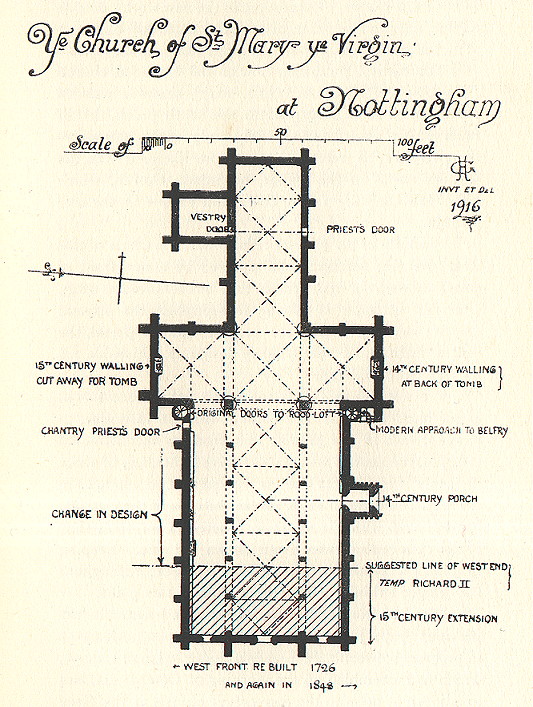

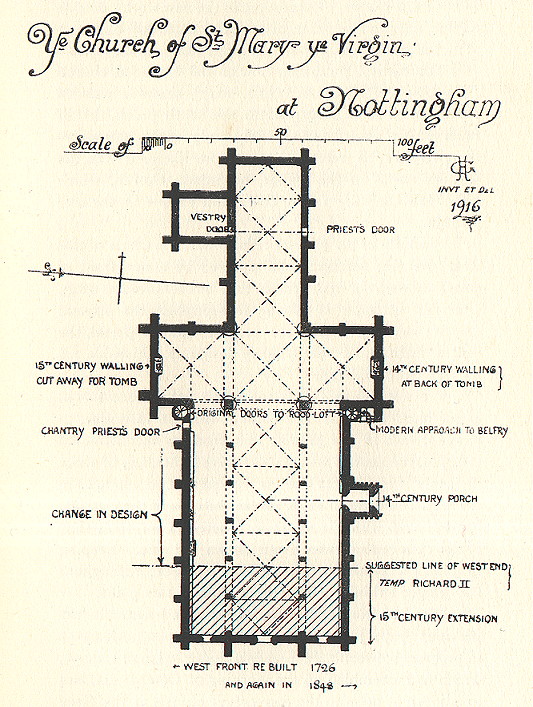

The analysis by Harry Gill, 1916

Harry Gill, a well known local architect of the earlier part of the

twentieth century (he died in 1950), made a detailed examination of the

church, which was published by the Thoroton Society (Gill, 1916). His

description, which accompanied the text of a guided tour given by the Rev.

A du Boulay Hill (Hill, 1916), opens with St. Mary's being - a fine

example of the "Indian summer of Gothic architecture".

In discussing the structural origins of the present church, Gill thought

that the gargoyle on the south aisle clerestory parapet was a possible "key

to the whole fabric". It occurs at a point where there is a break

of three inches (7.62 cm) in the line of the cornice, and a perceptible

change in the contour of the moulding. Thus, he argued, it was inserted to

mark the junction between the work of two distinct periods, for eastwards

of the gargoyle the work is executed in Gedling stone and westward in

Mansfield stone below the line of racking and magnesian limestone above.

His text has "Gedling" in both instances, but I assume

that his sketch was correct and that has "Mansfield" on

the western side. In 1761 - the south aisle was "re-faced with

Derbyshire stone, the porch alone being left". This was repaired

in Roman cement which had crumbled off by 1916. Gill noted that the south

(clerestory?) wall was recased with Derbyshire stone in 1817. On stone,

Beckett (1977) writes of Wollaton, Trowell and Carlton for well-cemented

Coal Measures sandstones; Bulwell for magnesian limestone and lime; and

Gedling for the softer, more workable Triassic weatherstone.

Gill regarded all the earlier work as found on the eastward side, with a

portion of the south aisle including the porch, the eastern bay of the

north aisle including the chantry-house doorway, the lower portion of the

transept walls, including the canopied south transept tomb, and the two

stairway turrets, all being contemporaneous; with their details all being

of the fashion of the closing years of the 14th century. He particularly

mentioned the panelling in the gables and buttresses and the predominance

of foliated ogival arches; the decorative sculpting on the south porch

(replicated by Scott on the west porch), which is typical of the reign of

Richard II, especially lions' faces; also, he draws attention to the

description by Thoroton (in 1677) of ancient glass in the south aisle,

which included the arms of Samon, the Archbishops Arundel and Nevill

(1374-88), and Richard II. The glass he presumed was lost when the "new

tracery was made in 1761".

Internally,

he felt the tomb canopies themselves added evidence. The south transept

canopy is an integral construction with the transept, whereas the north

tomb is set into the wall, with clear cutting away of the original

structure. The south canopy obviously matches the south porch and is of

the style fashionable in the reign of Richard II (1377-1399). The north

canopy, however, is of the style of Edward IV (1461-70 & 71-83) with "Yorkist"

roses in the tracery which tops the now-empty niches. Edward IV, who

proclaimed himself King at Nottingham, and his brother, Richard III, spent

much time in the city. If the canopied south transept tomb is that of a

Samon, the options are John Samon the elder, died ca. 1395, or his son

John (whom Thoroton had described as "the benefactor of St.

Mary's"), who died in 1416, and Gill noted that the tomb could

have been erected within their lifetime. He suggested that the western

limit of the church during that era may have been one bay west of the

south porch, which would have placed the porch in the traditional place.

Referring back to Rev. Hill's talk he draws attention to a Papal

Indulgence of 1401, designed to draw in money to continue the work "newly

begun with solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work". The

westward extension then could have been built while the initial west end

was in situ. The west porch, now Scott and Moffatt's reproduction of

1845-8, was shown in the 1677 print to closely resemble the still-existing

but well-worn south porch and Gill pondered whether it was not in fact

moved from its original position at the end of the shorter first-phase

building.

Internally,

he felt the tomb canopies themselves added evidence. The south transept

canopy is an integral construction with the transept, whereas the north

tomb is set into the wall, with clear cutting away of the original

structure. The south canopy obviously matches the south porch and is of

the style fashionable in the reign of Richard II (1377-1399). The north

canopy, however, is of the style of Edward IV (1461-70 & 71-83) with "Yorkist"

roses in the tracery which tops the now-empty niches. Edward IV, who

proclaimed himself King at Nottingham, and his brother, Richard III, spent

much time in the city. If the canopied south transept tomb is that of a

Samon, the options are John Samon the elder, died ca. 1395, or his son

John (whom Thoroton had described as "the benefactor of St.

Mary's"), who died in 1416, and Gill noted that the tomb could

have been erected within their lifetime. He suggested that the western

limit of the church during that era may have been one bay west of the

south porch, which would have placed the porch in the traditional place.

Referring back to Rev. Hill's talk he draws attention to a Papal

Indulgence of 1401, designed to draw in money to continue the work "newly

begun with solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work". The

westward extension then could have been built while the initial west end

was in situ. The west porch, now Scott and Moffatt's reproduction of

1845-8, was shown in the 1677 print to closely resemble the still-existing

but well-worn south porch and Gill pondered whether it was not in fact

moved from its original position at the end of the shorter first-phase

building.

Turning to the Chancel, Gill described this as built of Gedling stone,

probably after the main church was completed. The relative simplicity of

construction he noted as at odds with the main body and from the "slender

angle shafts" on the eastern edge of the tower piers concluded

that the window form of the main church was intended to continue but did

not. Gill thought the tower was built in the reign of Henry VII

(1485-1509), arguing that it could not have been built prior to completion

of the chancel as there would have been insufficient strength in the lower

structure. Something which only he has noted is the presence of the strong

"relieving" or "discharging" arch

within each face of the tower just above the line of the roofs, designed

to place the downward force onto the massive tower piers. The lower lights

of the east and west faces of the tower were modified and the stone "stringing"

altered in 1807 to accommodate the clock made by Thomas Hardy of

Nottingham. To complete his description, Gill provided a speculative plan

of the building when first complete (right).

To summarize, what Gill argued was that there was an intact "Samon"

church, of around 1390, the building of which disrupted a "Commission

of Inquiry" meeting in the church in 1386 (Borough Records), and

that building was extended during the 15th century. Further, he claimed

that further evidence of the piecemeal construction comes from the

inexactitude of the building lines - adding that he felt the buttresses on

the north aisle are not exactly opposite those of the south aisle and

neither set is in line with the piers of the nave arcades. Moreover, the

buttress designs are more elaborate on the south side. The two westernmost

windows of the north aisle match those of the south aisle in general

proportions and shape but have four lights (sections) as opposed to the

three lights of the south aisle. The eastern windows of the north aisle

again differ in detail of the stonework. The south aisle windows he

compares with those at St. Peter's and local "18th century Gothic"

but noted that the south wall was recased with Derbyshire stone in 1817.

According to Hill, the piers of the arcades are lozenge-shaped in plan,

with the shorter diameter between the arches, and shallow arch-moulds

carried down without capitals, which "suggest a date of about

1470-80, and cannot be ascribed to any time much earlier than that period".

He then gave his opinion as to the likely master builder as being one with

knowledge of York Minster, much of which was built contemporaneously with

St. Mary's.

Observations by Close, 1866

Both De Boulay Hill and Gill drew on the earlier article by T. Close,

who wrote on "St. Mary's Church, its probable architect and

benefactors" (in Allen, 1866, pp. 105-120). Close plumped for

William of Wykeham due to what he thought was similarity with Winchester

Cathedral. As for dates, he drew on Deering's descriptions of the armorial

shield in the windows, accepting the time of Richard II (1377-99) and Anne

of Bohemia (died 1394) adding - "Details of a peculiarly shaped

doorway in the north aisle, leading to what is now a receptacle for coals,

but which formerly - was probably a separate - perhaps a mortuary chapel;

of later date though than that of the nave, to which it is attached. Its

hood moulding terminates in two sculptured heads, both crowned - male and

female - and both unfortunately mutilated". He concluded these

heads were "I believe, the likenesses of Richard II and Anne of

Bohemia" drawing comparison with a monument in Westminster Abbey,

so, the stone was "proof of pre 1394". Much of Close's

article was reiterated in the first Guide Book (Anon. 1874), which

includes the illustrations of the shields seen by Deering (see later).

Close was able to explain those of The Earls of Arundel and Surrey as

Thomas de Arundel was Archbishop of York, 1388-96, then of Canterbury,

1396-1414, as well as being Lord Chancellor of England no less than five

times. Two other shields were those of Richard II, King of England before

his first marriage, January 1382, and probably his shield after that

marriage to Anne of Bohemia. That made good sense as Richard II was often

at Nottingham. The fourth shield, however, posed a puzzle which Close

could not fully decipher. He determined that the arms thereon were those

of the Nevill family but could not identify a member of the family who had

known or sensibly likely close associations with Nottingham. The closest

candidate he could find was Alexander de Nevill, "a devoted

friend of Richard II", who was Archbishop of York in 1374-87, but

there was the problem that Alexander was no friend of Thomas de Arundel.

Counter-credence, however, came from Nottingham being both in the Primacy

and Diocese of York, with the Archbishop having a palace at Southwell, and

it would not be surprising for there being an Archbishop's arms in a

window denoting founders.

Continue

Continue  References

References  Return to History Introduction

Return to History Introduction

Compiled by Brian Taylor, published September 2000

stmarys/2ws&anx2.htm

Internally,

he felt the tomb canopies themselves added evidence. The south transept

canopy is an integral construction with the transept, whereas the north

tomb is set into the wall, with clear cutting away of the original

structure. The south canopy obviously matches the south porch and is of

the style fashionable in the reign of Richard II (1377-1399). The north

canopy, however, is of the style of Edward IV (1461-70 & 71-83) with "Yorkist"

roses in the tracery which tops the now-empty niches. Edward IV, who

proclaimed himself King at Nottingham, and his brother, Richard III, spent

much time in the city. If the canopied south transept tomb is that of a

Samon, the options are John Samon the elder, died ca. 1395, or his son

John (whom Thoroton had described as "the benefactor of St.

Mary's"), who died in 1416, and Gill noted that the tomb could

have been erected within their lifetime. He suggested that the western

limit of the church during that era may have been one bay west of the

south porch, which would have placed the porch in the traditional place.

Referring back to Rev. Hill's talk he draws attention to a Papal

Indulgence of 1401, designed to draw in money to continue the work "newly

begun with solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work". The

westward extension then could have been built while the initial west end

was in situ. The west porch, now Scott and Moffatt's reproduction of

1845-8, was shown in the 1677 print to closely resemble the still-existing

but well-worn south porch and Gill pondered whether it was not in fact

moved from its original position at the end of the shorter first-phase

building.

Internally,

he felt the tomb canopies themselves added evidence. The south transept

canopy is an integral construction with the transept, whereas the north

tomb is set into the wall, with clear cutting away of the original

structure. The south canopy obviously matches the south porch and is of

the style fashionable in the reign of Richard II (1377-1399). The north

canopy, however, is of the style of Edward IV (1461-70 & 71-83) with "Yorkist"

roses in the tracery which tops the now-empty niches. Edward IV, who

proclaimed himself King at Nottingham, and his brother, Richard III, spent

much time in the city. If the canopied south transept tomb is that of a

Samon, the options are John Samon the elder, died ca. 1395, or his son

John (whom Thoroton had described as "the benefactor of St.

Mary's"), who died in 1416, and Gill noted that the tomb could

have been erected within their lifetime. He suggested that the western

limit of the church during that era may have been one bay west of the

south porch, which would have placed the porch in the traditional place.

Referring back to Rev. Hill's talk he draws attention to a Papal

Indulgence of 1401, designed to draw in money to continue the work "newly

begun with solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work". The

westward extension then could have been built while the initial west end

was in situ. The west porch, now Scott and Moffatt's reproduction of

1845-8, was shown in the 1677 print to closely resemble the still-existing

but well-worn south porch and Gill pondered whether it was not in fact

moved from its original position at the end of the shorter first-phase

building.